Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela

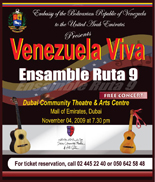

Embassy in the UAE

Indigenous ProgrammesVenezuela and Indigenous Rights Indigenous Peoples Today, Venezuela has a small but diverse Indigenous population that mostly lives far from the capital city of Caracas on the country's border regions with Guyana, Brazil, and Colombia. Numbering only about 1.5 percent of Venezuela's 23 million people, they are divided into about 28 different ethnic groups. The largest group, with about 200,000, is the Wayúu (also known as the Guajíra) who live in the state of Zulia on the Colombia border. Smaller groups live in the southern and eastern states of Amazonas, Bolívar, Delta Amacuro, Anzoátegui, and Apure. In addition to the Wayúu, these groups include the Warao, Pemón, Añú, Yanomani, Jivi, Piaroa, Kariña, Pumé, Yekuana, Yukpa, Eñepá, Kurripakao, Barí, Piapoko, Baré, Baniva, Puinave, Yeral, Jodi, Kariná, Warekena, Yarabana, Sapé, Wanai, and Uruak. In 1989, these diverse peoples formed the Venezuelan National Indian Council (Consejo Nacional Indio de Venezuela, CONIVE). President Nicia Maldonado, a Yekuana, notes that the organization was born as a popular struggle in the context of the "Caracazo" riots in 1989 against the government's neoliberal reforms: IMF mandated oil price hikes that caused a popular uprising that caused dozens dead. Out of a small office in Caracas, their elected staff presses their concerns on both the national and international levels. Maldonado notes that their gains have not been easy, and that they have been achieved due to years of community struggles. Constitutional Reforms Since Venezuela gained independence from Spain in 1821, Indigenous and African peoples had always been held in a subjugated position, including being justified out of the country's constitutions. After years of organizing social movements at the grassroots level, Indigenous peoples gained a significant political victory with the codification of many of their rights in the 1999 constitution. It expressed an inclusive Bolivarian thought that, in the words of an Indigenous delegate to the constitutional assembly, incorporated Indigenous and African peoples "from the preamble to the final transitionary articles." Article 9 of this new constitution declares that while Spanish is Venezuela's official language, "Indigenous languages are also for official use for Indigenous peoples and must be respected throughout the Republic's territory for being part of the nation's and humanity's patrimonial culture." Chapter VIII details the rights and responsibilities of Indigenous peoples. In particular, Article 119 recognizes the social, political, and economic organization of Indigenous communities, as well as their cultures, languages, rights, and lands. Specifically, land rights are collective, inalienable, and non-transferable. This is a critical provision; given that historically Indigenous peoples throughout Latin America have lost much of their territorial base through confiscation for the nonpayment of debts, many of which were often illegally imposed by surrounding white landholders. On October 12, 2003, the government announced a new ambitious national campaign to provide legal titles for traditional Indigenous land holdings. Subsequent articles pledge that the government will not engage in extraction of natural resources from native lands without consultation with Indigenous groups or in a manner that would harm their cultures or economy. Furthermore, the local Indigenous population must benefit from this extraction. This is significant because governments have long exploited Indigenous lands for their wealth (hydroelectric power in Chiapas, oil in Ecuador, uranium in South Dakota, etc.) without consideration for the often disastrous impact it has on the local inhabitants. The constitution also defends the preservation of and respect for ethnic identities, traditional religions, and medicinal practices. Furthermore, it allows for the development of bilingual education programs that reflect Indigenous values and traditions. It defends Indigenous intellectual property rights, and abolishes 'bio-piracy' that extracts Indigenous resources and knowledge for foreign benefit with nothing being returned to local communities. Article 125 proclaims an Indigenous right to political participation in the government, including representation in the National Assembly. Unlike what is often called the "dead letter of the law" in which positive-sounding legislation brings no real benefits for the intended population, these constitutional revisions have significantly improved the lives of Indigenous peoples in Venezuela. Most visibly, three Indigenous representatives (Noelí Pocaterra, José Luis González, and Guillermo Guevara, all long-time activists) were elected to the National Assembly and other leaders have assumed positions of authority in government. Never before has this previously marginalized population enjoyed such recognition and rights. The government's dedication to Indigenous rights is also reflected in its ongoing program to translate this constitution into all of Venezuela's languages. |